Typography As Theming in the Ol' West.

After leaving Great Falls, it was back on the road through Montana, into Wyoming, and on to South Dakota. How do we know we're in the Old West? In absence of covered wagons, dusty trails, and cowboys on horseback rounding up cattle...the typography.

I have a huge soft spot for nineteenth century American wood type. These garish display faces which originated in England during the 1820s and 30s have become possibly the most evocative visual expression of the Old West in the eyes of the public.

And why? Well, as with all aspects of thematic design, it's the strong connection to life in the cinematic mode.

Opening titles of two very popular and long-running television Westerns.

These "WANTED POSTER" slab serifs, fat faces, and circus type resonate so strongly because of their representation (signage, props and ephemera, even titles and credits) within the Western genre in film and television.

An authentic WANTED poster for John Wilkes Booth (1865), and one for the "Frito Bandito" (1968).

And also advertising, and many other forms of vernacular graphic design. If you want to say "Old West" as simply and boldly as possible, wood type as used on broadsides in the 1800s is the way to go.

For the first sixty years of the twentieth century, the Western was the most popular genre in American visual media. This (largely fantasy) Old West was so thematically important, both nostalgically and aspirationally, that Walt Disney included its expression—Frontierland—as one of the five core environments of his Disneyland concept.

To the trained designer, some of these forms as reproduced in a contemporary context feel visually apocryphal. Although hand lettering was set on curves during the 1800s, the execution of SALOON here smacks of the 'flag' warp effect in Adobe Illustrator. What gives it away is the distortion of the individual characters. But the average person is not likely to notice.

Something I found fascinating on some of the signage I encountered on this road trip was the collision of first generation (late 1800s) historical nods with second generation (1950s) retro-Western interpretations. Here "CACTUS CAFE LOUNGE" is rendered in a fairly authentic Tuscan, or what we might think of as circus type. Yet "Western Hospitality" is in the kind of cheesy lasso rope script you'd associate with Roy Rogers and Howdy Doody. Adobe's Giddyup typeface is one of the more recent takes on this look.

"What idiot dressed you in that outfit?"

This collision of the 'real' Old West with the mid-century retro pop version is one of the best jokes in Back to the Future Part III (1990), when Doc dresses Marty in what he thinks is the best 1955 version of what he should be wearing when he travels back in time to 1880. Marty is (of course) mocked, beaten, and nearly hanged for his outfit after he arrives.

Western type also collides with virtually any typographic style that was popular when the sign was made; in this case, it's most likely the 1940s through the 1960s. As Route 66 gave way to the interstate highway system throughout the western states, tourism (and the associated roadside attractions) soared. Here the "See" is classic mid-century, chamber of commerce boosterism. Funnily, the extraneous exclamation point on BEARS! is authentic to both nineteenth century broadside advertising and the 1950s equivalent.

Western wood typography is also employed out of context. I found this coffee roaster in Frankenmuth, Michigan, a town with a Bavarian theme. All the rest of the type I saw was heavily Germanic; the sort of blackletter, storybook fantasy-esque lettering which you would expect. But this is a Tuscan wood type style. I think the intention here—and I've seen this before with wood type—is to connote authentic, old-fashioned quality. If the sign is old and American looking, the coffee must taste more 'real' than what Starbucks offers across the street. This kind of marketing is what Andrew Potter calls the "authenticity hoax" in his book of the same name.

Although most of the lettering I found was rendered in the last fifty years, every now and then there were some great examples of authentic, antique hand lettering along the way. This sign in Deadwood, South Dakota appeared to date to the late nineteenth or early twentieth century.

Here the typeface is correct, but the method of manufacturing is too recent. This is direct print, like the kind of sign you'd see on a storefront in any stripmall in the country.

Here a fat French Clarendon mingles with some bold grotesque type. Mixing slabs with sans serifs is actually very true to nineteenth century printing, but I'm guessing here it's serendipity rather than a desire for period authenticity; grotesque/gothic faces were back in vogue at mid-century.

I'm glad I made it too! Wall Drug in South Dakota provided a wealth of lovely lettering. This sign is mid-century but hand painted in the traditional way.

Some of these signs were in the "so bad it's good" category. This ugliness borders on grace.

When the typeface looks right, and the hand painting appears authentic, I tend to think the sample predates the mid-century Western pop revival. This is probably from the 1920s or 30s.

Again to the trained eye, this type screams computer manipulation.

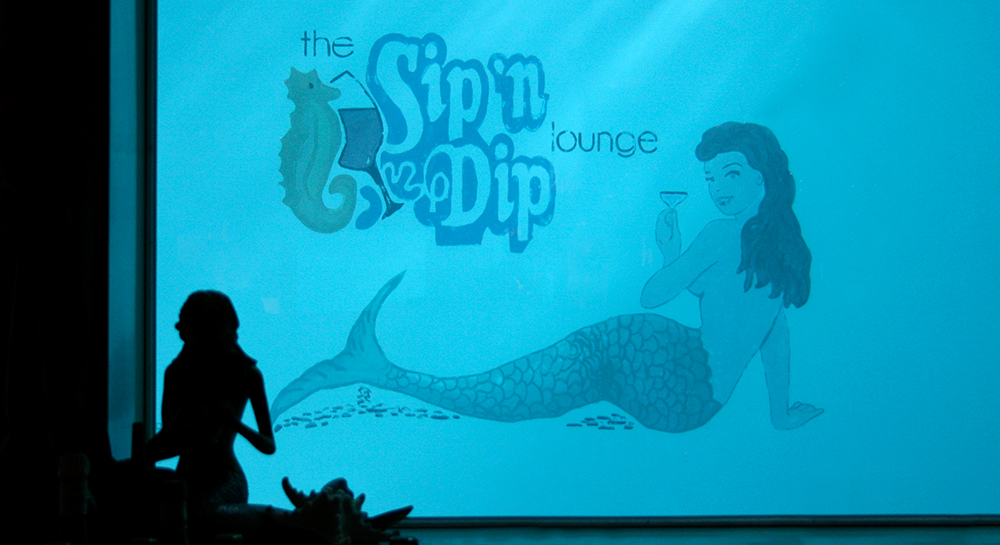

Circus type in neon! Unlike above, the technological incongruence here is charming. I'm used to seeing this sort of thing in Las Vegas; here it's inside a gas station above the beer coolers.

Many styles of typography are well recognized by the public. Elegant script faces, for example, connote luxury goods because they look and feel "French" and communicate "royalty." Helvetica says "no nonsense." Cooper Black says "kids sneakers" (or perhaps, if you're old enough, Pet Sounds). But I'd venture that nineteenth century wood type lettering and the Old West it is recognized for is probably the largest, widest, deepest piece of American mental real estate that typography could possibly claim.

Because of such extensive usage throughout the past century in popular visual media, it's in the water. It's part of our DNA as American consumers. As a component of thematic design, you don't just see it roadside. Wood type will be found at any venue that calls for an Old West flair; restaurants, bars, casinos, hotels, roller coasters and other such attractions, whole Frontierlands (as at the Disney Parks), even entire theme parks (Knott's Berry Farm, Silver Dollar City, Dollywood, et al).

As such, it's self-perpetuating at this point. Even if a young person has never seen a Western film or television show, they've undoubtedly been to one of those restaurants, walked around one of those theme parks, ridden one of those rides, stayed at one of those motels.

I'll end here with some more of my favorite examples from this past summer's trip. Can you guess the vintage of each? Which ones are painted and which ones are printed? Pre-computer or post? Or do they all blend together into a singular Old West...

Perhaps all wood type that is solid melts into air.