DCA Then and Now - Part 1: How to Make an Entrance.

Although I’ve visited the Disneyland Resort many times since, I hadn’t done any actual site documentation there since 2008. In the summer of 2021 I spent four days at the resort catching up as best I could. So much had happened in terms of design changes, particularly in the last decade, that I struggled to capture it all. Ultimately I decided to focus on major new developments, and look at other various alterations with a “then and now” approach.

DCA original entrance, 2008.

Postcard from the Edge

The most drastic of these alterations have been made to Disney California Adventure (DCA), which opened to disappointing reviews and lackluster attendance in February, 2001. For years the Disney designers—whose vision had to be drastically scaled back due to corporate budget cuts—were frustrated with the park’s poor performance.

Disney’s California Adventure 2001 park map. Ⓒ Disney Enterprises, Inc.

Put indelicately, this “second gate” at the Disneyland Resort was done on the cheap. Visitors complained that it was a half-day park at best (yet the same price as Disneyland next door) with too many restaurants and not enough attractions. It was built on the site of the former Disneyland parking lot, prompting late Disney Imagineer John Hench to viciously quip, “I liked it better as a parking lot.”

Disney’s California Adventure 2001 souvenir park map poster. Ⓒ Disney Enterprises, Inc.

At opening, DCA was comprised of four lands: Sunshine Plaza, Hollywood Pictures Backlot, Paradise Pier, and Golden State. This last one was divided into six distinct themed areas which the designers referred to as “districts”—Condor Flats, Grizzly Peak Recreation Area, Golden Vine Winery, Bountiful Valley Farm, Pacific Wharf, and The Bay Area.

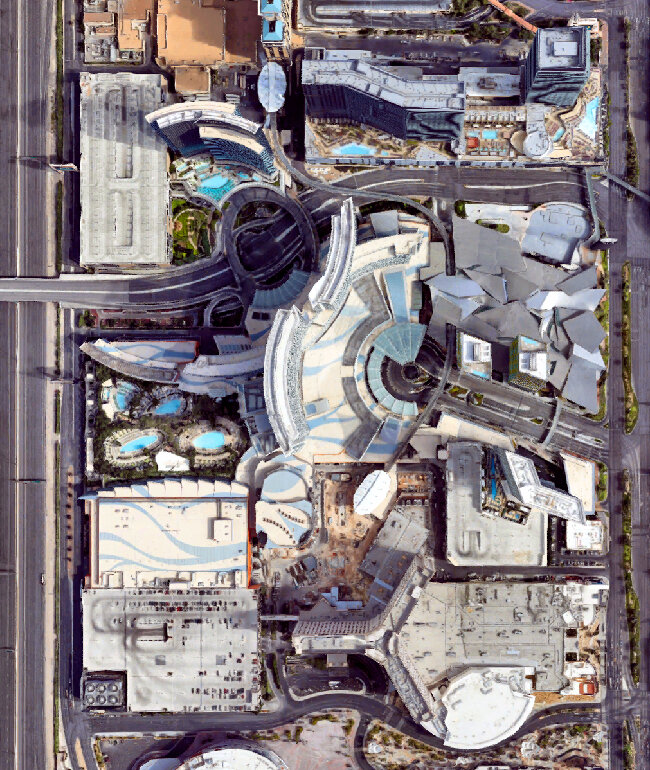

The shape of California over the original park layout. Underlay map data: Ⓒ Google.

Arguably the only clever concept the original park’s designers came up with was that each of these four lands and six “districts” were laid out together in roughly the shape of the state of California. As my overlay demonstrates, it’s a bit exaggerated and not literal. Yet the locales of the various themed areas align rather well.

In the twenty years since the park has been added on to and modified possibly more than any other theme park on the planet. And these changes started right away. DCA’s original dark ride, Superstar Limo, didn’t even last a whole year. A Bug's Land opened in the fall of 2002. Then more additions in 2004 and 2008. Change after change, right through to the present.

DCA original entrance, 2008.

Perhaps the most obnoxious original element was the park’s entrance. I’m not sure what the designers were thinking, but the idea was supposed to be a kind of abstracted journey into a stylized tourist postcard of California. It might have seemed nifty on paper, but as an actual environment it totally flopped.

Which was sort of to be expected. It’s sitting right next to Disneyland! As The Imagineering Field Guide to Disney California Adventure (an official Disney publication) put it honestly, yet delicately:

The park was originally envisioned as a counterpoint to Disneyland—a different offering with a distinct tone and selection of experiences intended to provide variety for guests at the resort. But the proximity of Disneyland pointed out that there are elements of the Disney Park experience at Disney California Adventure—in its original incarnation—did not possess.

The Sun Icon, 2008.

And the park’s original visual magnet, or “wienie” as Walt Disney called it? It was the Sun Icon, which looked like a giant hubcap mounted above a wave fountain. Yes, that was the official name. The Sun Icon. In the 2019 Disney+ streaming series The Imagineering Story, designers like Kevin Rafferty were quite honest in their reappraisal of the mistakes they made. Said Rafferty of the Sun Icon:

Much to our chagrin, it didn’t adhere to our fundamental design principles of theme park design. The first statement that you saw when you walked into the gate was the sharp sun. Frankly you could have seen that at a shopping mall in Newport Beach. It’s like, ‘Why is it here?’

The Sun Icon in Sunshine Plaza, 2008.

The thing was actually so ugly that I took very few pictures of it back in 2008. Here you can see Sunshine Plaza as it was called through the park’s original Golden Gate Bridge.

DCA’s Original Golden Gate Bridge, 2008.

This stretched iconic bridge build around the original Disneyland Monorail track was cartoonish and silly. This is what was supposed to compete with the original Disneyland Park, mere steps away?

Abstracted and bland Sunshine Plaza on 2001 park map. Ⓒ Disney Enterprises, Inc.

As I detail in my studio courses in thematic design, in order for these environments to be experientially successful, a degree of immersion is required. And immersion works best when the presentation is literal. In other words, immersion can be measured on a gradient of abstraction. The less abstract (more literal) a space is, the more immersive it will be, and thus the most experientially successful.

DCA original entrance, 2008.

This original entrance was a total abstraction. Too garish, too brash, and moreover, didn’t immerse people as they entered the park. The bridge especially comes off like an oversized toy. Honey, I Shrunk the Guests?

DCA original ceramic mural, east side, 2008.

Flanking either side of the bridge was what Disney advertised as the “largest ceramic mural in the world.” This was part of the stylized postcard landscape that guests were supposed to be entering.

DCA original ceramic mural, west side, 2008.

Again I thought the thing was pretty ugly, so I didn’t take many pictures of it. Fortunately, over at Yesterland there is a good record with many detailed close up shots.

Welcome to Buena Vista Street

What DCA needed was an entirely new approach, something thematically appropriate to compliment Disneyland right next door. The designers realized, the only way to compete with the original Disneyland was to compliment it. In 2007 they announced that the park would basically get its very own version of Main Street U.S.A.

After extensive planning and two years of construction, an entirely new themed land for Disney California Adventure, Buena Vista Street, opened on June 15, 2012. Sunshine Plaza, the Sun Icon and its wave pool, and the cartoonish Golden Gate Bridge were all torn out. In place of all that now is a detailed and immersive environment—in my opinion some of the most successfully rendered placemaking that the company has ever executed. I will detail this land across two posts.

Buena Vista Street preview event, June 10, 2012.

I was actually on Buena Vista Street for a Disneyland Annual Passholder (AP) preview event five days prior to the public opening. Here you can see the construction walls still up.

Organic and pleasant Buena Vista Street on 2021 Park Map. Ⓒ Disney Enterprises, Inc.

The land is named after the street that the Walt Disney Studios is on. Note the powerful use of asymmetrical balance, and how the entry corridor dog-legs to the right and leverages some classic conceal-and-reveal to place the central fountain off to one side. The entire area feels organic, and although spotlessly clean in the Disney fashion, gives the impression of having been built over time.

Pan-Pacific Gate

A new entrance gate and turnstiles for California Adventure had opened exactly one year prior to Buena Vista Street. The original 11 foot high CALIFORNIA letters were relocated to Cal Expo in 2012, the fairground where the 18-day California State Fair is held annually.

Pan-Pacific Auditorium, closed and neglected, mid-seventies. Wikimedia / Public Domain.

The new gate was designed to evoke perhaps the classic example of Streamline Moderne architecture in Los Angeles (and one of the finest ever to be built in the United States), the Pan-Pacific Auditorium. It’s an inspired choice, as the structure was designed by LA architectural firm Wurdeman and Becket. Welton Becket, you’ll recall, was the neighbor of Walt Disney who advised him to hire his own “Hollywood people” and form his own in-house design consultancy (WED Enterprises, later Walt Disney Imagineering). In the late 1960s, Welton Becket Associates designed Disney’s Contemporary Hotel at Walt Disney World (WDW).

After closing in 1972, the Pan-Pacific Auditorium fell into decay and finally burned down in 1989.

Looking closely you can see how well the designers adapted the contours of the auditorium. But are guests fully immersed? Not yet. This is just a bit of Streamline moderne, with only tenuous aesthetic connection to what lies inside.

Then again the entry gates of Disneyland across the way only begin to suggest a Victorian Gingerbread styling that will be more fully realized once inside the park. It’s a tease, and it doesn’t make literal sense in the context of the design of Main Street U.S.A. The same could be said for DCA’s new entrance.

Pan-Pacific Auditorium entrance to Disney-MGM Studios, 2007.

This wasn’t a new idea however. When Disney-MGM Studios (now Disney's Hollywood Studios) opened back in May of 1989 at Walt Disney World, the park featured a nearly identical entrance gate (ironically this was just three weeks before the original auditorium would burn down). One major difference is that the Studios park gate includes ticket sales windows and also functioning neon. The same structural motif is also used for the more recently built entrance to the Disney's Hollywood Studios parking lot. As we’ll see, this isn’t the only element that the design team would lift from that Florida park.