Kingdoms of Artifice - Part 1: Oregon Zoo.

This past summer I embarked on site research of a different kind. In 2022 I signed a contract with Dr. Benjamin George at Lexington Books, an academic imprint of Rowman & Littlefield. Our monograph, Disney and the Theming of the Contemporary Zoo: Kingdoms of Artifice, is for their new Studies in Disney and Culture line. Benjamin is an associate professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at Utah State University. We learned earlier this year that Lexington has been acquired by Bloomsbury, a leading publisher of visual arts and design titles. This means Kingdoms of Artifice will reach an even wider and more appropriate audience.

Expedition Everest at Disney’s Animal Kingdom, 2007.

I’ve been collaborating with Benjamin since he contacted me in 2019 over our common interest in theming. This has blossomed into a mutual interest in zoo design and Disney’s impact on that industry in the wake of the opening of Animal Kingdom at Walt Disney World in 1998. From our book proposal:

The opening of Disney’s Animal Kingdom introduced the design principles of the theme park to the display of wildlife. In the decades since, zoo designers the world over have adopted Disney’s approach in theming both the visitor and the animal experience. With Kingdoms of Artifice we critically examine how post-Disney zoo environments combine entertainment with education and complexify authenticity with theatricality.

The village of Harambe at Disney’s Animal Kingdom, 2007.

During a year-long sabbatical and beyond, Benjamin has visited over 30 zoos around the world and interviewed zoo design practitioners and even Disney Imagineers. Thus far, he has amassed over 4,000 pages of transcripts and thousands upon thousands of photos.

One place he couldn’t get to was the Pacific Northwest. In 2023, I received the Paul G. Windley Faculty Excellence and Development Award from the University of Idaho, a $1,000 grant which recognizes three consecutive years of excellence in faculty scholarship and provides support for continuing scholarly activities in written research and dissemination. Funded by this award, in July 2024 I visited the Oregon Zoo in Portland, Oregon and the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, Washington.

Oregon Zoo

The Oregon Zoo dates all the way back to 1888 and is the oldest in the United States west of the Mississippi. In 1925, the zoo moved to the current site of the Portland Japanese Garden and again in 1959 to its present location within a small valley still in Washington Park. At about 64 acres, the zoo is the most popular attraction in the state.

The zoo’s footprint is an organic shape consisting of multiple elevation levels. The varied terrain adds an element of realism to the various habitat areas and their landscaping. The zoo is small enough to be comfortably manageable in a single-day visit.

Entry Plaza

In the spring of 1998—right as Disney’s Animal Kingdom (DAK) opened—a new entrance plaza debuted at the highest level of the site. The zoo was also connected to Portland’s MAX light rail system via the new underground Washington Park Station later that same year.

This new entrance significantly altered how visitors orient themselves to the zoo and begin their visit. It’s heavily themed to the Pacific Northwest with a series of lodge buildings that recall the nation’s National Parks. There is a large outdoor foyer area between the ticket purchase gate and entrance. To the left is the zoo’s primary gift shop and to the right is a restaurant, restrooms, and lockers.

The cafe’s CASCADE GRILL sign is set in Berthold Block, a typeface family dating back to the early twentieth century and in use at the Disney theme parks for years. The barn lighting, sconces, surface treatments, and painting scheme are all very, very Disney.

Great Northwest: A Unique (and Local) Beginning

Opening along with this new entry area was a completely new way to begin a day at the Oregon Zoo—by starting with the region’s local ecosystems and species. In this way visitors begin with that which is most familiar and then as they navigate and weave their way through the site, everything becomes increasingly exotic. One starts in the grand temperate rain forests of the Pacific Northwest and before you know it, you’re on the plains of Africa.

A Native American presence is introduced immediately, with examples of Northwest Coast art and large totem poles. The landscaping appears to be a blend of Washington Park’s natural vegetation and deliberate plantings.

Immersion exhibits begin as you turn the corner, and they seem to employ a blend of natural and artificial rock work. Only with a trained eye can you spot the difference by looking closely. The safety barriers here are rustic and practical.

Yet directly ahead is what appears to be a mountain highway.

The barrier rails on either side look exactly like those you can find all across the state. The subtle suggestion is that if visitors walked this way, a car might come barreling right towards them.

I thought this was quite clever. With the new 1998 entrance, the circulation path became quite prescribed as one-way. Although I suspect it’s not vigorously enforced (and for photo purposes I definitely trekked the wrong direction more than once, if only for a moment), how do you encourage people to walk the right way, or more to the point, discourage them from heading where you don’t want them to? A themed highway was the answer.

In case the highway barriers weren’t obvious enough, an arrow points to the left. Here the design vernacular of the National Forest system is explicitly replicated with the same shape language, typography, and colors. As I’ve detailed prior, Disney has done this at both their theme parks and hotel resorts.

Following the design of the entry plaza, the entire Great Northwest Trail area is intended to appear to be within a federal or state park. The barriers, decking, and shelter structures literally place visitors in a setting that is familiar to and comfortable for locals. This detailed theming thus reframes the zoo’s entrance as being part of a larger outdoor lifestyle and ties it to the experience of living in the region.

Signage follows the conventions one would expect to find elsewhere in recreation areas throughout Oregon. Although the animals are safely contained within immersion habitats, the verbiage presumes they are all in the wild.

A series of bridges break up the different parts of the trail. The walk down this zone was steep. Climbing back up and winding through the rest of the zoo, however, is gradual. This grading plan is well-considered; the longer your day, the more tired you—and your kids—are likely to get. Completing the one-way loop to return to the entrance is not difficult.

The path descends gradually into a dense forest. The highlights here are the bears, bald eagles, and fish—all staged at unique elevation levels. The hardscape and railings suggest we could be walking through any state park in the country.

And yet, here in the hardscape is something Disney has done for years. There are faux animal tracks imprinted into the concrete.

And also artificial fallen trees. A few of them are used as viewing portals into animal enclosures. This provides a fun and immersive experience for younger visitors. I saw more than one child crawling in to get a closer look. Moments like these turn the zoo into a playground while still feeling natural. Trees do fall in the forest, after all.

To access the eagle habitat, visitors walk through a covered wooden bridge which traverses a canyon stream bed. Of all the zones at the zoo, this first area felt the most immersive because many of the trees were already here; the designers simply and seamlessly integrated bridges, paths, and wildlife viewing areas.

As with using the National Parks vernacular, this is smart. The designers start with what people already know and what they see right outside their city or town everyday in Oregon or Washington. The bridge appears to be very much like what you’d drive through in the countryside, yet scaled down for pedestrians.

Within some of the interior viewing areas, didactic displays are themed to be part of rural sheds. The shape language and material choices harmonize with the covered bridge.

This first Pacific Northwest zone functions much like, in software terms, the onboarding for the Oregon Zoo visitor experience. All the interaction points are introduced—the enclosures, photo spots, touch samples, and reader rails. After proceeding through this first zone everyone can read, essentially, the text of the zoo.

Close to exiting the area, I came across a bear viewing enclosure which highlights their relationship to bees and honey. The shed roof suggests a warehouse of some kind.

There are vintage fruit crate label reproductions—what Disney calls ghost graphics, or subtle pieces of graphic design that contribute to a sense of place. Also stacks of prop honey boxes and barn lighting fixtures which are commonly found in their theme parks.

Family Farm

At the tail end of the Great Northwest section, the landscape flattens out and leads to a farm. Many zoos feature a livestock petting area. Here the theme is classic Midwestern red-and-white, something many American children are intimately familiar with from storybooks.

This is something I had never bothered to look into, but apparently the traditional paint scheme is related to European traditions and also red was simply cheaper. It’s another example of thematic design harnessing a visual grammar that is already known to the public.

The hand washing station looks like a well with themed pipes and spigot-style water faucets.

These are the kinds of antique details a zoo could easily skip, but Disney never does.

Across the path opposite appears to be a back-of-house structure. It is themed, again, to a Midwestern small town, all in white planking. Even though it’s likely just office space, the implication is that the fictional family which owns the farm lives here.

Africa

I’m limiting my visual survey to those areas of the Oregon Zoo where thematic design is most evident. Naturally, there’s an Africa section, which most Western zoos typically incorporate into their layouts. The habitat and exhibit elements here span roughly 1989–2007, augmented over time, and you can tell what’s most recent based on how Disneyized it is.

The entry signage for AFRICA didn’t surprise me at all, but was still disappointing. Since the 1990s designers have substituted Carol Twombly’s Lithos (1989) as a “good enough” substitute for the German wood typeface Neuland (1923), familiar to many as the logo lettering from the film Jurassic Park (1993) and used in tropical, exotic settings ever since. I’ve seen both Lithos and Neuland in wildlife preserves, zoos, aquariums, and water parks. Anywhere there’s a jungle.

Nothing says Africa like thatched huts. It’s not necessarily lazy, but theming needs to communicate cultural motifs at a glance, just like a Hollywood backlot set.

Sometimes they are used for signage and graphics.

Other times you can sit in them.

After thatch, the other common sign of Africa-ness is the shed. These are sometimes used for retail and refreshment locations but more commonly employed for back-of-house structures.

These rustic touches are contrasted with the area’s large aviary.

The exterior is quite modern, and the dark material choices are appropriate for the Pacific Northwest.

You can view the aviary from inside an adjacent restaurant, which I did while eating lunch. The bay window panes provided expansive, unobstructed vistas.

Inside, theming takes over. Fencing and barriers all appear to have been constructed by the local population. Uneven, rough-hewn logs with rope and leather ties.

The designers could have kept the interior as modern as the outside, but chose not to. These small moments provide heightened immersion and serve to place visitors within a different ecosystem with its own human construction language and materials vocabulary.

Just outside, I noticed a large artificial baobab tree sculpted in the Disney style. On some of the upper limbs, real trees have been grafted on and live shrubs are visible. It’s basically a massive concrete planter. These newer additions to the Africa area demonstrate that zoo-ness is increasingly defined by the Disney approach.

Where possible, utility fencing is disguised by natural materials such as bamboo.

Other barriers are more detailed and real wood is used.

These “castaway, deserted island shipwreck” rope ties were imported directly from Disney. You can find them all over the Frontierland and Adventureland areas of their parks around the world, implying everything from pirates to Tom Sawyer. Did fences like this exist at zoos before Disney? I doubt it.

Sometimes they collide with modern safety barriers, here in the case of thick glass.

A few parts of the Africa section were clearly older. You can tell by the lack of overall architectural detail and narrative cues.

When more natural materials such as rough logs and rope ties are used, it’s a sign that theming was added on later.

The older parts of this temple-like enclosure are generically Asian. Here I found Torii Gate-style supports all painted dark brown.

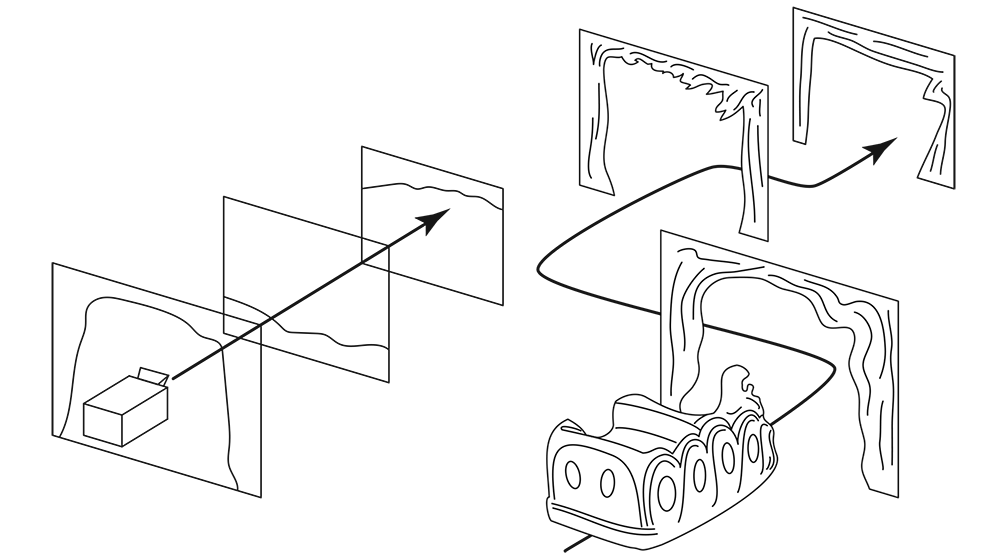

One display in particular reminded me of a Disney dark ride vehicle. In the predator habitat, an actual vintage Landrover safari jeep has been cut in half.

It’s both a photo op and a visitor experience. There are prop crates on the floor for getting into the driver seat, passenger side, and rear of the vehicle.

The jeep has been mounted so that its windshield lines up directly with the glass barrier of the enclosure. The animals water and feed in the shade right outside.

A savannah mural is painted on the three walls behind. It’s a very effective illusion, especially for young children.

You sit behind the steering wheel and if you keep your vision narrow and look straight ahead, it appears that you’ve just driven right into the habitat.

I watched several school groups circulate through. It’s a popular spot.

There is one true ride at the Oregon Zoo. One of the last things I did was board the 5/8 scale, 30-inch narrow gauge Washington Park and Zoo Railway which costs a separate $5 ticket. As it was added when the zoo moved in 1958–59, the Disneyland influence is explicit. The line is a single long loop which features a trestle arc at one end and a curved tunnel at the other just before you return to the station. The railroad used to connect the zoo with another part of the park via a longer route which closed in 2013, and there is currently a movement to restore its original transportation function.

Overall the Oregon Zoo was a pleasant experience, and its design demonstrates the ways in which theming can be used to successfully frame and guide the visitor experience.

A new Draft Campus Plan for the site was unveiled in January 2024. Developed in partnership with CLR Design, a leading exhibit and habitat architectural firm based in Philadelphia, on the plan it remains to be seen what new thematic elements—if any—will be added. I certainly look forward to seeing what their designers come up with.